When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it’s truly the same? The answer lies in pharmacokinetic studies-the most common and trusted method used worldwide to prove that a generic drug behaves identically in the body. Yet calling it the "gold standard" is misleading. It’s not perfect. It’s not always enough. And for some drugs, it’s barely even the best tool we have.

What Pharmacokinetic Studies Actually Measure

Pharmacokinetic studies track how a drug moves through your body. Specifically, they measure two key things: how fast the drug reaches its peak concentration in your blood (called Cmax), and how much of it gets absorbed over time (called AUC, or area under the curve). These numbers tell regulators whether the generic version delivers the same amount of medicine, at the same speed, as the original brand.The rules are strict. For most oral drugs, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of generic to brand must fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand drug gives you an AUC of 100 units, the generic can’t be below 80 or above 125. If it’s outside that range, the drug won’t get approved. For high-risk drugs like warfarin or digoxin-where even a small difference can cause serious harm-the window tightens to 90-111%.

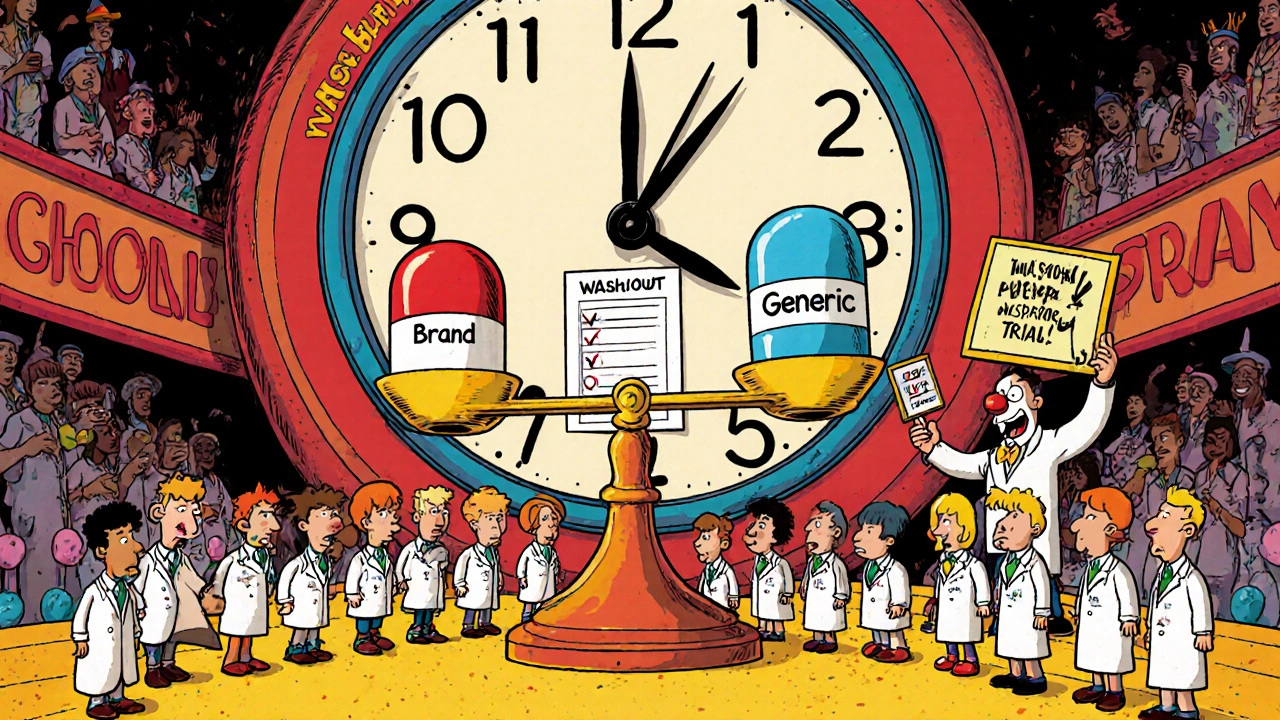

These studies aren’t done in patients. They’re done in healthy volunteers-usually 24 to 36 people-under tightly controlled conditions. Participants take the brand drug one day, then the generic another, with a washout period in between. Half the group takes the brand first; the other half takes the generic first. This crossover design cancels out individual differences in metabolism.

Why This Method Became the Default

The system we use today was set in motion by the U.S. Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before that, generic companies had to run full clinical trials to prove their drugs worked. That cost millions and took years. Hatch-Waxman changed everything. It said: if the generic has the same active ingredient, strength, and dosage form as the brand, and if it behaves the same in the body (as shown by pharmacokinetic studies), then you don’t need to prove it works again. You just need to prove it’s absorbed the same way.This shortcut saved billions and made generics widely available. Today, over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. The FDA approved 95% of generic applications in 2022 using this method. Globally, more than 50 countries follow similar rules, often aligned with WHO and ICH guidelines.

The Hidden Flaws: When Pharmacokinetics Don’t Tell the Whole Story

Here’s the problem: two drugs can have identical Cmax and AUC values and still behave differently in the body.Take gentamicin, an antibiotic. A 2010 study in PLOS ONE found that two generic versions-both passing pharmacokinetic tests and matching the brand in every lab test-still showed different effects in patients. Their therapeutic outcomes weren’t the same, even though their blood levels looked perfect. Why? Because the drug’s effectiveness depends on how it interacts with bacteria, not just how much gets into the blood. Pharmacokinetics can’t measure that.

Another issue: complex formulations. Modified-release pills, inhalers, topical creams, and injectables don’t always follow simple absorption rules. A generic cream might deliver the same amount of drug into the bloodstream as the brand-but if it doesn’t penetrate the skin deeply enough, it won’t treat eczema properly. That’s why dermatopharmacokinetic (DMPK) studies and in vitro permeation tests are now being used for topical products. One study showed these methods were more accurate than clinical trials involving hundreds of patients.

And then there’s food. Some drugs absorb poorly on an empty stomach. Others need food to work. Pharmacokinetic studies test both fasting and fed states-but even that doesn’t catch every interaction. A minor change in excipients (inactive ingredients like fillers or coatings) can alter how a pill breaks down in the gut. That’s why the FDA has over 1,800 product-specific guidances. No two drugs are treated the same.

What About In Vitro Tests? Could They Replace Human Studies?

You might think: if we can test the drug in a lab, why do we need people at all? For some drugs, the answer is yes.The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) groups drugs based on solubility and permeability. If a drug is BCS Class I-highly soluble and highly permeable-then in vitro dissolution tests can predict how it will behave in the body. The FDA now accepts these tests as a waiver for bioequivalence studies for certain drugs. That cuts costs and time dramatically. But this only works for about 15% of all drugs.

Even more promising: physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. These computer simulations predict how a drug moves through the body based on anatomy, physiology, and chemistry. The FDA has accepted PBPK models to approve generics for some BCS Class I drugs since 2020. It’s not magic-it’s math. But it’s getting smarter. In the future, we may see fewer human studies and more simulations, especially for drugs with predictable behavior.

Cost, Time, and the Real Burden on Manufacturers

Running a pharmacokinetic study isn’t cheap. It costs between $300,000 and $1 million. It takes 12 to 18 months from formulation to approval. For small companies, that’s a huge barrier.And it’s not just about money. The science is tricky. A change in particle size, coating thickness, or even the type of lubricant used can throw off absorption. One manufacturer told regulators they spent two years tweaking a single generic tablet just to get the dissolution profile right. And even then, they had to run multiple bioequivalence studies.

That’s why experts recommend early engagement with regulators. If you know your drug fits BCS Class I, ask for a waiver before spending a million dollars. Use dissolution testing early. Build data that supports your case. Don’t wait until the last minute.

Regulatory Differences Around the World

The U.S. FDA and the European EMA don’t always agree. The FDA uses product-specific guidances-meaning each drug has its own rules. The EMA tends to use a one-size-fits-all approach. That creates headaches for global manufacturers. A generic that passes in the U.S. might fail in Europe because the testing conditions differ.Some countries, especially in emerging markets, lack the labs, staff, or funding to run proper studies. That’s why counterfeit or substandard generics still show up. The WHO tries to harmonize standards, but enforcement is uneven. The result? Patients in some countries get safe generics. Others get risky ones.

The Future: Beyond Blood Levels

The field is shifting. We’re moving away from the idea that one test fits all. For NTI drugs, we now require tighter limits. For topical drugs, we’re using skin penetration tests. For complex injectables, we’re turning to advanced analytical tools. For some drugs, we’re using PBPK models instead of human trials.Pharmacokinetic studies aren’t going away. They’re still the backbone of generic approval. But they’re no longer the whole story. The real gold standard isn’t a single test. It’s the right test for the right drug.

What matters most isn’t whether a generic matches the brand in blood levels. It’s whether it keeps patients safe and healthy. And sometimes, that means looking beyond the bloodstream entirely.

Are pharmacokinetic studies always required for generic drugs?

No. For certain drugs classified as BCS Class I-those that are highly soluble and highly permeable-the FDA and other agencies may waive human pharmacokinetic studies. Instead, they accept in vitro dissolution testing as proof of equivalence. This applies to roughly 15% of all generic drugs. For others, especially complex formulations like extended-release tablets or topical creams, additional testing is required.

Why do some generic drugs cause different side effects than the brand?

While the active ingredient is the same, inactive ingredients (like fillers, dyes, or coatings) can differ between brands and generics. These can affect how quickly the drug dissolves or is absorbed. For most people, this doesn’t matter. But for patients with sensitive systems or those taking narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin, even small differences can lead to changes in effectiveness or side effects. That’s why pharmacokinetic studies include both fasting and fed conditions-to catch these variations.

Can a generic drug pass bioequivalence testing and still be unsafe?

Yes. There have been documented cases where generics passed all pharmacokinetic tests but still produced different clinical outcomes. One example involved gentamicin, where two generics with identical blood levels showed different antibacterial effects. This happens because pharmacokinetics measure absorption, not biological activity. For drugs that act locally (like inhalers or creams) or require interaction with specific targets (like antibiotics), additional testing is needed beyond blood concentration.

What’s the difference between bioequivalence and therapeutic equivalence?

Bioequivalence means two drugs have similar absorption rates and levels in the blood. Therapeutic equivalence means they produce the same clinical effect-same benefits, same risks. Bioequivalence is a proxy for therapeutic equivalence, but it’s not guaranteed. Two drugs can be bioequivalent but not therapeutically equivalent if they interact differently with the body’s systems. That’s why regulators are moving toward more targeted testing for complex drugs.

How do regulators decide which testing method to use for a new generic drug?

Regulators like the FDA and EMA use product-specific guidances based on the drug’s characteristics. Is it immediate-release or extended-release? Is it taken orally or applied to the skin? Does it have a narrow therapeutic index? Is it highly soluble? Based on these factors, they choose the best method: pharmacokinetic studies, dissolution testing, in vitro permeation tests, or even computer modeling. There’s no universal rule-it’s tailored to the drug.

Comments (13)

edgar popa

14 Nov, 2025generic pills work fine for me, i’ve been takin em for years. dont see why we need all this fancy science if the price is low and i dont feel any diff.

Eve Miller

14 Nov, 2025It is deeply irresponsible to suggest that pharmacokinetic studies are 'not enough.' The 80-125% bioequivalence range is statistically rigorous, peer-reviewed, and validated across decades of clinical use. To imply otherwise is to undermine public trust in regulatory science.

Chrisna Bronkhorst

16 Nov, 2025Let’s be real. The FDA approves 95% of generics using PK studies because it’s cheap and fast. The real problem? They don’t test for long-term effects or real-world variability. Patients are the lab rats.

Amie Wilde

17 Nov, 2025i get why people freak out about generics but honestly? most of the time it’s the excipients messing with their stomach, not the drug itself. just dont take it on an empty stomach if you’re sensitive.

Gary Hattis

17 Nov, 2025As someone who’s worked in pharma across three continents, I’ve seen how messy this gets. In India, generics are lifesavers. In Europe, they’re over-regulated. In the US? It’s a lobbying circus. The science isn’t broken-it’s being bent by profit and politics.

Esperanza Decor

18 Nov, 2025Why do we still rely on 24 healthy volunteers? That’s less than the size of a typical high school class. What about elderly patients? People with liver disease? The system was built for ideal cases, not real humans.

Deepa Lakshminarasimhan

18 Nov, 2025They’re hiding something. PK studies only measure blood levels. What if the brand drug has a secret ingredient that makes it work better? Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know. They profit from the confusion.

Erica Cruz

20 Nov, 2025Oh wow, another article pretending the FDA isn’t a corporate puppet. Newsflash: if a generic passes PK testing, it’s approved. Doesn’t matter if it kills people slowly. Profit over patient. Classic.

Johnson Abraham

20 Nov, 2025so like… if the pill looks different and costs less, but the blood test says it’s the same… then why do i feel weird on it? 🤔 maybe the system is just dumb

Shante Ajadeen

22 Nov, 2025Thank you for explaining this so clearly. I’ve always wondered how generics are approved. It’s reassuring to know regulators are adapting with new methods like PBPK modeling. We need more of this thoughtful progress.

dace yates

22 Nov, 2025Has anyone looked at whether generic antibiotics like gentamicin actually reduce infection rates in real hospitals? Or just whether blood levels match?

Danae Miley

23 Nov, 2025Yes, and that’s exactly why therapeutic equivalence studies are needed for narrow therapeutic index drugs. The current framework is outdated for complex formulations. Regulatory agencies must prioritize outcome-based metrics over surrogate biomarkers.

Charles Lewis

24 Nov, 2025While the pharmacokinetic model has served as a foundational pillar for generic drug approval, it is imperative that we recognize its limitations in an era of increasingly complex therapeutics. The transition from a one-size-fits-all bioequivalence paradigm to a drug-specific, mechanism-informed regulatory framework is not merely advisable-it is ethically and scientifically necessary. The integration of in vitro dissolution profiling, physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling, and patient-centric outcome metrics must be accelerated through international collaboration and investment in next-generation analytical platforms. We owe it to patients to move beyond blood concentrations and toward true therapeutic fidelity.