When a pharmacist hands you a generic pill instead of the brand-name drug your doctor prescribed, you might wonder: is this really the same thing? It’s not just a label swap. There’s a rigorous, science-backed system in place - one that pharmacists follow every single day to make sure the generic version won’t just work, but will work exactly like the original.

What Makes a Generic Drug Equivalent?

It’s not enough for a generic drug to have the same active ingredient. It has to deliver that ingredient to your body in the same way, at the same rate, and in the same amount. That’s where three layers of equivalence come in.Pharmaceutical equivalence means the generic has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form (pill, injection, cream), and route of administration (oral, topical, etc.) as the brand-name drug. Simple enough.

Bioequivalence is where the science gets serious. The generic must show that it releases the drug into your bloodstream at nearly the same speed and to nearly the same total level. The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for two key measurements - the maximum concentration in blood (Cmax) and the total exposure over time (AUC) - must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug. That’s not a guess. It’s a statistical threshold built on decades of data showing that within this range, there’s no meaningful difference in how the drug works in the body.

For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin, levothyroxine, or lithium - the window tightens to 90-111%. Even small changes here can cause harm. That’s why these drugs get extra scrutiny.

Therapeutic equivalence is the final stamp. It means the generic can be substituted without any expected change in safety or effectiveness. This isn’t just about chemistry. It’s about real-world outcomes.

The Orange Book: The Pharmacist’s Bible

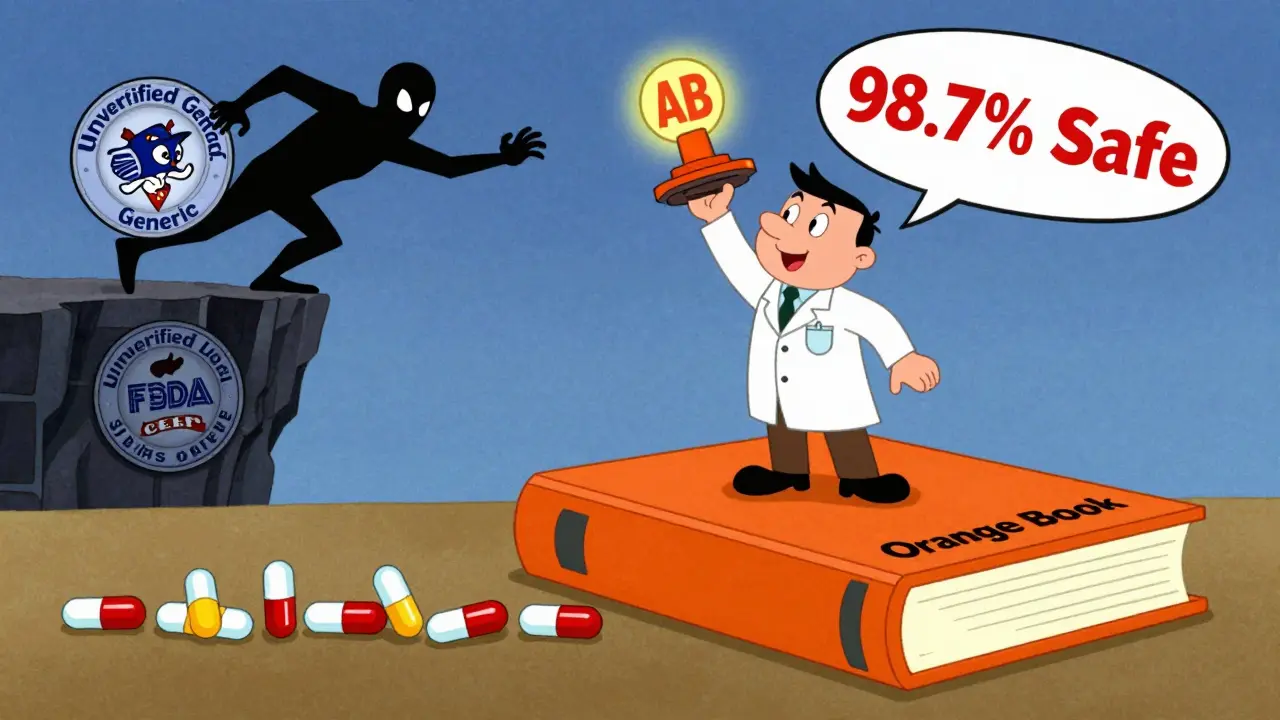

The Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations - better known as the Orange Book - is the single most important tool pharmacists use to verify this. Published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, it’s updated monthly and contains data on over 16,500 drug products as of April 2024.Each entry has a two-letter code. If you see AB, that’s the gold standard. It means the product has been shown to be both pharmaceutically and bioequivalent to the brand-name reference drug through human studies. In 2023, 98.7% of rated products carried an AB rating. That’s nearly every generic you’ll ever get.

Other codes tell you more: AN for nasal aerosols, AO for oral solutions, AT for topical products. These aren’t just labels - they tell pharmacists how the product was tested and whether substitution is safe.

Products rated B are flagged as not therapeutically equivalent. That could mean the data isn’t strong enough, or the formulation is too different. Pharmacists don’t substitute these without a prescriber’s explicit okay.

How Pharmacists Use the Orange Book in Practice

It’s not a complex ritual. It’s a fast, repeatable process - done in under 12 seconds per prescription, according to time-motion studies.Here’s how it works:

- Identify the reference drug - the original brand-name product listed in the prescription.

- Match the active ingredient, strength, and dosage form - no surprises here. If the brand is 10mg tablet, the generic must be exactly the same.

- Check the TE code - only an ‘A’ rating (usually AB) means substitution is allowed.

- Confirm no ‘Do Not Substitute’ note - if the prescriber wrote DAW (dispense as written), the pharmacist must honor it, even if the generic is rated AB.

Most pharmacists use the FDA’s free Orange Book mobile app, downloaded over 450,000 times as of March 2024. Others rely on integrated pharmacy systems like PioneerRx or QS/1 that pull Orange Book data directly into their dispensing software.

According to a 2023 survey of over 8,400 pharmacists, 98.7% check the Orange Book daily. Only 62.7% use commercial databases like Micromedex or Lexicomp - and even then, they treat those as backups, not replacements.

Why the Orange Book Is the Law, Not Just a Guide

Every state in the U.S. - except Massachusetts - has laws that require pharmacists to use the Orange Book as the official source for determining therapeutic equivalence. Texas Administrative Code §309.3(a) says it plainly: pharmacists must use the Orange Book “as a basis for determining generic equivalency.”And it’s not just policy. It’s legal protection.

In 2019, a pharmacist in Texas was sanctioned after substituting a generic that wasn’t listed in the Orange Book. The court ruled that relying on internal company guidelines - not the FDA’s official source - was a breach of professional standards. That case, State Board of Pharmacy v. Smith, set a precedent. Use the Orange Book, or risk liability.

That’s why training is non-negotiable. 92.4% of pharmacies train new hires on Orange Book use, typically with 2-4 hours of instruction. After training, 89.3% of pharmacists correctly identify therapeutic equivalence - a high rate, but one that still means 1 in 10 could slip up without ongoing reinforcement.

What Happens When the Orange Book Doesn’t Have the Answer?

About 5.7% of generic substitutions involve drugs not yet listed in the Orange Book. That’s usually because the application is still under review, or the product is new or complex.For these, pharmacists turn to the FDA’s Non-Orange Book Listed Drugs guidance. They look at the ANDA submission data, compare labeling, and consult with prescribers if needed. But they never guess. If there’s no clear, documented equivalence, they dispense the brand or hold the prescription until clarification.

This is especially true for complex products - inhalers, topical creams, injectables - where traditional blood-level testing doesn’t fully capture how the drug behaves in the body. The FDA has issued over 1,850 product-specific guidances to help with these cases, but pharmacists still need to tread carefully.

Is the System Perfect?

Critics point out real gaps. Dr. Randall Stafford from Stanford noted in a 2021 JAMA Internal Medicine article that for inhalers or topical drugs, measuring blood levels doesn’t always reflect what’s happening at the site of action. The FDA agrees - and is investing $28.5 million through GDUFA III to develop better testing methods for these complex products.But here’s the thing: even with those gaps, the system works.

A 2020 FDA meta-analysis of over 1 million patient records found no meaningful difference in adverse events between brand and generic drugs: 0.78% vs. 0.81%. That’s statistically the same.

And the numbers speak for themselves. In 2023, generics made up 90.7% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. - 8.9 billion pills. That’s a $12.7 billion annual savings in healthcare costs - all made possible because pharmacists can trust the Orange Book.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists put it best: the system has a documented substitution error rate of just 0.03% when properly followed. That’s better than most safety protocols in healthcare.

The Future: Biosimilars and Beyond

The next frontier isn’t small-molecule generics - it’s biosimilars. These are complex biologic drugs, like insulin or rheumatoid arthritis treatments, that are copies of other biologics. They’re not chemically identical. They’re made from living cells, so even tiny changes can affect performance.The FDA’s Purple Book - the biologics equivalent of the Orange Book - currently lists only 47 of the 350 approved biosimilars as therapeutically equivalent. That’s a big gap. Pharmacists are still learning how to interpret these listings, and many prescribers aren’t yet comfortable allowing substitution.

But the framework is there. The same principles apply: equivalence must be proven, documented, and verifiable. The Orange Book model is being adapted. The FDA is working on clearer labeling and more transparent data. Pharmacists will be on the front lines again - verifying, questioning, and ensuring safety.

For now, the system holds. It’s not flashy. It’s not glamorous. But every time a pharmacist checks the Orange Book, they’re protecting patients - and saving billions - with a simple, science-based step.

What does an 'AB' rating in the Orange Book mean?

An 'AB' rating means the generic drug has been proven to be both pharmaceutically equivalent (same active ingredient, strength, dosage form) and bioequivalent (absorbed into the bloodstream at the same rate and extent) as the brand-name reference drug. This is the highest level of therapeutic equivalence and allows for automatic substitution by pharmacists, unless the prescriber has marked 'dispense as written'.

Can pharmacists substitute generics without a doctor’s permission?

Yes - but only if the generic is rated 'A' in the Orange Book and the prescriber hasn’t written 'dispense as written' or 'no substitution' on the prescription. In 49 U.S. states, substitution is permitted by law when these conditions are met. Massachusetts is the only state that doesn’t allow automatic substitution, requiring prescriber approval every time.

Why do some generics have different shapes or colors than the brand name?

The active ingredient, strength, and delivery method must match - but inactive ingredients like fillers, dyes, and coatings can differ. These affect appearance, taste, or how fast the pill dissolves, but not how the drug works in the body. The FDA requires that these differences don’t impact safety or effectiveness. That’s why the Orange Book focuses on therapeutic equivalence, not looks.

Are generic drugs less effective than brand-name drugs?

No. The FDA requires generics to meet the same strict standards as brand-name drugs for quality, strength, purity, and stability. A 2020 FDA analysis of over 1 million patients found no statistically significant difference in adverse events between brand and generic drugs. Studies show generics perform within 5% of the brand in absorption and effectiveness - well within the accepted 80-125% bioequivalence range.

What happens if a generic isn’t listed in the Orange Book?

If a generic isn’t listed, pharmacists cannot assume it’s therapeutically equivalent. They must check the FDA’s Non-Orange Book Listed Drugs guidance, review the ANDA application data, and consult with the prescriber before substituting. In most cases, they’ll dispense the brand-name drug unless the prescriber confirms the generic is acceptable. Never substitute based on internal pharmacy lists or manufacturer claims alone.

How often is the Orange Book updated?

The Orange Book is updated monthly with supplements and published as a new annual edition. Pharmacists should always use the most current version - either through the FDA’s free mobile app or integrated pharmacy software that auto-updates. Outdated versions can lead to incorrect substitution decisions.

What Pharmacists Should Do Next

If you’re a pharmacist: make sure your Orange Book access is current. Use the official FDA app or ensure your pharmacy system pulls live data. If you’re new to the job, ask for training - and don’t skip the competency checks. One wrong substitution can have real consequences.If you’re a patient: know that your pharmacist is following strict standards. If you’re ever unsure about a generic, ask. Ask why it’s being substituted. Ask if it’s rated 'AB'. Most pharmacists are happy to explain.

The system isn’t perfect. But it’s the best we have - and it works. Every day, millions of people get safe, effective, affordable medicine because pharmacists take the time to check the right book. That’s not just practice. That’s responsibility.

Comments (13)

eric fert

26 Jan, 2026Oh please. The Orange Book is just a glorified marketing tool. I’ve seen generics that made me feel like I swallowed a rock, and others that made me dizzy. The FDA’s 80-125% window? That’s not science, that’s corporate compromise. I’ve had patients switch and crash their INR levels on warfarin generics. They call it 'bioequivalent'-I call it Russian roulette with pills.

Curtis Younker

27 Jan, 2026This is actually one of the most reassuring things I’ve read all week. 🙌 Pharmacists are the unsung heroes of healthcare-checking that orange book like it’s their sacred duty. I used to be paranoid about generics too, but knowing they’re held to this level of scrutiny? It makes me trust the system. Keep doing what you’re doing, pharmacy folks-you’re saving lives AND money.

Henry Jenkins

27 Jan, 2026Fascinating breakdown. I’m curious though-what happens when a drug gets an AB rating but the patient reports a different reaction? Is there a feedback loop back to the FDA? Or is the system static once the rating’s assigned? Also, how often do pharmacists flag inconsistencies between the Orange Book and real-world outcomes? I’d love to see data on that.

Dan Nichols

29 Jan, 2026The Orange Book is the law not a suggestion and anyone who treats it like a suggestion is asking for trouble. You dont just substitute based on what some pharmacist thinks looks right. The 98.7 percent AB rating is a lie if you dont account for the fact that some manufacturers game the system with cherry picked studies. And dont get me started on the mobile app-its outdated half the time

Renia Pyles

31 Jan, 2026I’ve been on 12 different generics for my thyroid. Every time I switch, I feel like a lab rat. One month I’m exhausted, the next I’m sweating through my pillow. The Orange Book doesn’t care how I feel. It cares about numbers. But I’m not a number. I’m a person who can’t sleep because some chemist decided my pill is 'equivalent' even though my body screams otherwise.

Rakesh Kakkad

1 Feb, 2026This is a highly commendable exposition on the regulatory framework governing pharmaceutical substitution. The Orange Book represents a paradigm of evidence-based governance in healthcare. However, one must acknowledge that the statistical thresholds employed may not account for inter-individual pharmacokinetic variance, particularly in populations with differing metabolic enzyme expression such as CYP2D6 poor metabolizers prevalent in South Asian demographics.

Nicholas Miter

2 Feb, 2026Honestly? I didn’t even know about the Orange Book until last year. I thought generics were just cheaper versions. Turns out there’s a whole science behind it. My pharmacist showed me how to check the AB rating on the app-game changer. Now I ask for it every time. No judgment, no drama. Just knowing I’m getting what’s supposed to work. Small things matter.

Suresh Kumar Govindan

4 Feb, 2026The FDA is a corporate puppet. The Orange Book is a façade. The same companies that make brand drugs own the generics. The 'bioequivalence' studies? Conducted in healthy young men. Not the elderly. Not the chronically ill. Not people on polypharmacy. This is not safety. This is profit dressed in white coats.

George Rahn

5 Feb, 2026America’s healthcare system is a house of cards built on bureaucratic arrogance. The Orange Book? A monument to the myth of efficiency. We’ve replaced the dignity of individualized care with a spreadsheet that says 'close enough.' And yet we call this progress? We’re not saving money-we’re sacrificing trust. And trust, unlike a pill, cannot be replicated.

Ashley Karanja

5 Feb, 2026I’m a clinical pharmacist and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had to explain this exact process to patients who are terrified of generics. The bioequivalence criteria are so tightly regulated that even the excipients are monitored for potential interactions. The 0.03% substitution error rate? That’s lower than most hospital handoff protocols. And yes, the Orange Book is the gospel-but it’s the gospel backed by 40 years of pharmacokinetic data, not corporate spin. We’re not just checking boxes-we’re preventing harm.

Karen Droege

6 Feb, 2026I’ve worked in rural pharmacies for 18 years. I’ve seen people choose between food and meds. When I swap a $400 brand for a $4 generic and they cry because they can finally afford their insulin? That’s not bureaucracy. That’s justice. The Orange Book isn’t perfect-but it’s the only thing standing between people and financial ruin. Don’t hate the system. Hate that we need it at all.

rasna saha

7 Feb, 2026Thank you for explaining this so clearly. I used to worry every time I got a different-looking pill. Now I know it’s not about color or shape-it’s about what’s inside. And that’s what matters. You’ve helped me feel less anxious about my meds. 💙

Ashley Porter

9 Feb, 2026The Orange Book’s TE codes are a necessary evil. But the real issue is the lack of post-marketing surveillance for generics. Once it’s on the shelf, we rarely track outcomes. We assume equivalence. But real patients aren’t clinical trial subjects. We need longitudinal data-especially for CNS meds.