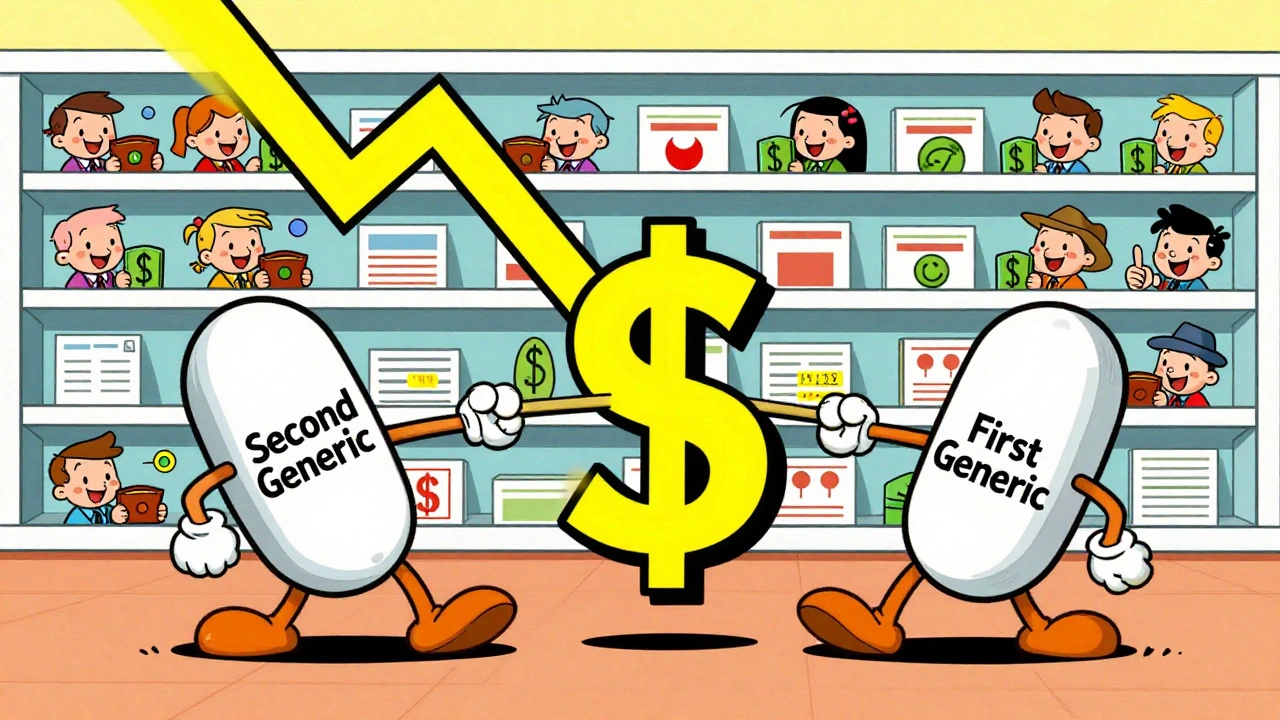

When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the first generic version usually hits the market at about 15% to 20% of the original price. That sounds like a big win. But here’s the real story: the biggest price drops don’t come from the first generic. They come from the second and third.

Why the second generic changes everything

The first generic maker gets a head start. They’ve done the paperwork, passed the FDA checks, and now they’re the only game in town. With no competition, they can charge a little more-sometimes up to 87% of the brand’s price. That’s still cheaper than the original, but far from rock bottom. Then comes the second generic. Suddenly, there are two companies selling the same pill. Neither wants to lose market share. So they start undercutting each other. Within months, prices plunge to around 58% of the brand’s cost. That’s a 30% drop in just a few months. It’s not magic. It’s basic economics: more sellers = lower prices. This isn’t theoretical. The FDA tracked over 1,000 generic drugs approved between 2018 and 2020. Their data shows that when a second generic enters, prices fall by an average of 36% compared to the first generic alone. That’s billions saved in just one year.The third generic is where prices really crash

Now imagine a third company joins. They’re not even trying to be the cheapest-they just need to get in the door. So they undercut the second. And the second has to respond. The result? Prices tumble again, down to 42% of the brand’s original price. That’s a 27% further drop from the second generic. Combined, the second and third generics cut prices by more than half from where they started after the first entry. For a drug that cost $100 a month as a brand, it’s now $42. For patients paying out of pocket, that’s a life-changing difference. The data doesn’t lie. A 2021 analysis by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that markets with three or more generic manufacturers saw prices fall by about 20% within three years. But the biggest savings happen right after the third entrant. That’s the tipping point.What happens when competition stalls

Not every drug gets a second or third generic. In nearly half of all generic markets, only two companies ever show up. That’s called a duopoly. And in those cases, prices don’t keep falling. They stabilize-or worse, rise. A 2017 study from the University of Florida looked at 150 generic drugs. In markets where competition dropped from three companies to two, prices jumped by 100% to 300%. Why? Because without a third player to force competition, the two remaining companies can quietly agree-not out loud, but through behavior-to hold prices steady. It’s not collusion. It’s just what happens when the market lacks enough players to keep each other honest. This isn’t rare. It’s common. And it’s why so many people still pay too much for pills they need.

Who’s holding back the third generic?

You’d think more companies would rush in when they see a $200 million market opening up. But they don’t. Why? First, the barriers are high. Getting FDA approval takes time and money. For complex drugs-like injectables or inhalers-it can cost millions just to prove your version works the same as the brand. Second, the supply chain is stacked against small players. Three big wholesalers-McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health-control 85% of the market. They decide which generics get shelf space. If they favor the big players, smaller companies get locked out. Third, brand companies fight back. They file dozens of patents, not to protect innovation, but to delay generics. One drug had 75 patents piled on over 18 years, pushing generic entry from 2016 to 2034. That’s not innovation. That’s legal obstruction. And then there’s “pay for delay.” That’s when a brand company pays a generic maker to stay away. The FDA estimates these deals cost patients $3 billion a year in higher out-of-pocket costs. In 2023, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association found that banning just these deals could save $45 billion over ten years.Who wins when third generics enter

Patients win. Lower prices mean fewer people skip doses or split pills. That reduces hospital visits and long-term health costs. Insurers win. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) like Express Scripts get better discounts when there are more generic options. More competition = more leverage. That means lower premiums for employers and individuals. Taxpayers win. Medicare and Medicaid spend billions on prescriptions. Every dollar saved on generics means more money for other care. Even the brand companies benefit in the long run. When generics drive down prices across the board, it forces innovation. Companies can’t just rely on patent extensions. They have to build better drugs.

What’s being done to fix this

The FDA is trying. Their GDUFA III program (2023-2027) is speeding up approvals for complex generics. That’s critical-those are the drugs where second and third entrants are hardest to come by. Congress passed the CREATES Act in 2022 to stop brand companies from blocking sample access. If a generic maker can’t get a sample of the brand to test against, they can’t even start the approval process. There’s also bipartisan support for the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act, which would ban “pay for delay” deals outright. If passed, it could unlock hundreds of new generic entries. But the real solution is simple: we need more competitors. Not just one. Not just two. Three, four, five. The more, the better.What you can do

If you’re paying for prescriptions out of pocket, ask your pharmacist: “Is there another generic version available?” Sometimes, a third maker exists but isn’t stocked. Request it. Pharmacies will order it if enough people ask. If you’re covered by insurance, check your plan’s formulary. Some plans limit which generics they cover. Push for broader access. More choices mean lower prices for everyone. And if you know someone who’s struggling to afford medication, share this: the cheapest version isn’t always the first one listed. The real savings come when the third company shows up.What’s next

Generic drug prices are expected to keep falling 3% to 5% per year through 2027-but only if competition stays strong. If consolidation continues-like the merger of Mylan and Upjohn into Viatris, or Teva buying Allergan Generics-there will be fewer players, not more. The Congressional Budget Office warns that without action, Medicare could lose $25 billion a year by 2030 to inflated generic prices. That’s not inevitable. It’s a choice. The science is clear: second and third generics are the most powerful tool we have to lower drug costs. No policy change, no negotiation, no rebate system comes close. It’s simple math: more companies = lower prices. The question isn’t whether we need more competition. It’s why we’re still letting it be blocked.Why do generic drug prices drop so much after the second or third company enters?

When only one generic is available, that company has little pressure to lower prices. But once a second company enters, they compete directly for market share by undercutting each other. The third company pushes prices even lower to get a foothold. This competition forces prices down dramatically-often to 40-50% of the original brand price. The FDA found that the third generic typically cuts prices an additional 27% beyond the second.

Can a drug have more than three generic versions?

Yes. In large markets with high demand-like common blood pressure or cholesterol drugs-10 or more generic manufacturers can enter. In those cases, prices often drop to 70-80% below the original brand price. The more competitors, the lower the price, as long as no single company controls too much of the market.

Why don’t more companies make generic drugs if the profits are so high?

Making generics isn’t as easy as it sounds. It requires FDA approval, which can cost millions and take years, especially for complex drugs like inhalers or injectables. Also, the supply chain is dominated by three big wholesalers and pharmacy benefit managers who favor big manufacturers. Smaller companies often can’t get shelf space or favorable contracts, making it hard to compete even if they get approved.

What are "pay for delay" deals, and how do they affect prices?

"Pay for delay" happens when a brand-name drug company pays a generic manufacturer to delay entering the market. Instead of competing, the generic company agrees to wait. This keeps prices high. The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association estimates these deals cost patients $3 billion a year in higher out-of-pocket costs. They’re legal in the U.S., but banned in some other countries.

How can I find out if a cheaper generic version exists for my medication?

Ask your pharmacist if there are other generic manufacturers for your drug. Sometimes the pharmacy only stocks one version, even if others are available. You can also check the FDA’s Orange Book online, which lists all approved generic versions. Or use apps like GoodRx to compare prices across different generic brands.

Comments (11)

Ignacio Pacheco

3 Dec, 2025So let me get this straight - we need a third generic just to get prices below 50% of the brand? And we’re acting surprised? This isn’t capitalism, it’s a rigged game where the FDA’s approval queue is the VIP line and only the rich get in.

Kidar Saleh

5 Dec, 2025The UK has seen this play out with statins and metformin. When five generics entered the market, prices fell to 95% below brand. The NHS doesn’t negotiate - it just mandates the cheapest. No middlemen. No PBMs. No patents on old molecules. It’s not magic. It’s policy.

Here in Europe, we don’t wait for patients to ask pharmacists. We automate it. The system chooses the lowest price. End of story.

Maybe it’s time we stop treating medicine like a luxury good and start treating it like a public utility.

Chloe Madison

7 Dec, 2025THIS IS SO IMPORTANT. I’ve seen friends skip insulin doses because the first generic was still $150. Then a third generic showed up - $32. They cried. Not from sadness - from relief. This isn’t just economics. It’s survival.

If you’re reading this and you’re on meds - ask your pharmacist. Ask again. Ask your doctor to write ‘dispense as written’ with the cheapest generic listed. You have power. Use it.

We can fix this. One pharmacy request at a time.

Vincent Soldja

8 Dec, 2025Third generics lower prices. That’s it.

Makenzie Keely

8 Dec, 2025Let me emphasize this: the third generic isn’t just a bonus - it’s the tipping point. The FDA’s data shows a 27% additional drop after the third entrant, and that’s not an outlier - it’s the pattern across hundreds of drugs. And yet, we’re still letting brand companies delay entry with patent thickets and pay-for-delay schemes? This isn’t innovation - it’s exploitation.

Also, GoodRx is your friend. I used it last month and found a third-party version of my blood pressure med for $12. My insurance was charging $48 for the same thing. I switched. No one at my pharmacy even knew it existed. They’re not hiding it - they’re just not telling you.

Share this. Talk to your pharmacist. Demand the third option. It’s not a favor - it’s your right.

Francine Phillips

10 Dec, 2025My mom’s cholesterol med went from $90 to $28 when the third generic came in. She didn’t even know there were three versions. The pharmacy just gave her the first one on the list. I had to call and ask. Took ten minutes. Changed her life.

Just saying.

Katherine Gianelli

11 Dec, 2025I’ve been a pharmacy tech for 14 years, and I’ve watched this play out over and over. The third generic doesn’t just drop the price - it changes how people live. People stop choosing between food and meds. They refill their prescriptions. They get their blood pressure under control. They go back to work.

And the worst part? Most pharmacists don’t even know which generics are available unless they’re asked. We’re trained to fill, not to educate.

If you’re reading this and you’re on meds - ask. Ask like your life depends on it. Because it does.

Joykrishna Banerjee

12 Dec, 2025LOL. You think this is about competition? Nah. It's about rent-seeking behavior in a neoliberal monoculture. The real issue is the commodification of biological necessity - a Marxist critique of pharmaceutical capitalism, bro. The third generic is just a symptom. The disease is profit-driven healthcare. Also, India produces 70% of the world's generics - but you won't hear that from Big Pharma's PR machine. 🤡

Myson Jones

13 Dec, 2025It’s interesting how market forces can drive down costs when left to operate - but only if the barriers to entry aren’t artificially inflated. The real problem isn’t the lack of generics - it’s the lack of a level playing field.

Maybe we need to reframe this not as a drug issue, but as a market access issue.

parth pandya

15 Dec, 2025thats so true i had a friend who was payin 200$ for metformin then a 3rd generic came and it was 12$ he was so happy but no one told him it exsisted. the phamarcy just gave him the first one. also the fda orange book is hard to use but goodrx is way easier

Albert Essel

15 Dec, 2025One thing I’ve learned from working in public health: price isn’t just about affordability - it’s about dignity. When a patient can finally afford their medication without choosing between rent and refills, they stop being a statistic and become a person again.

The third generic isn’t just a business detail. It’s a moral turning point.