When you pick up a prescription at your local drugstore, you might not think twice if the pill looks different than last time. That’s retail pharmacy substitution in action - a routine, often invisible part of how medications reach patients. But if you’ve ever been hospitalized, you’ve likely encountered a completely different kind of substitution - one that doesn’t happen at the counter, but in meetings, through electronic alerts, and with input from doctors, nurses, and clinical pharmacists. The differences between how retail and hospital pharmacies handle medication substitution aren’t just technical; they reflect two entirely different systems of care, each with its own rules, goals, and risks.

How Retail Pharmacies Handle Substitution

Retail pharmacies, like CVS, Walgreens, or your neighborhood independent drugstore, are designed for speed, volume, and cost control. When a prescription comes in for a brand-name drug like Lipitor, the pharmacist doesn’t need to ask a doctor. Under state law, they can automatically swap it for the generic version - atorvastatin - unless the prescriber wrote "Do Not Substitute" or the patient refuses. This is called generic substitution, and it’s the backbone of outpatient medication access.

In 2023, retail pharmacies filled over 5.8 billion prescriptions. Of those, 90.2% involved generic substitution. That’s not because pharmacists are pushing generics - it’s because insurance plans require it. Most plans won’t pay full price for brand-name drugs when a cheaper, therapeutically equivalent generic exists. Pharmacists are caught between the system and the patient. One pharmacist in Ohio told a patient, "I can’t override your insurance’s refusal to cover the brand," only to have the patient return two days later with a new script after the doctor filed a prior authorization.

Each state has its own rules. Thirty-two states require pharmacists to verbally notify patients when substitution happens. Eighteen require written consent for the first substitution. The rest rely on printed notices or pharmacy policy. But no matter the rule, the process is transactional: prescription arrives, pharmacist checks formulary, swaps if allowed, hands over the bottle. The patient walks out. No follow-up. No clinical review.

That’s why patient confusion is common. A 2023 Consumer Reports survey found 14.3% of patients didn’t realize they’d been switched to a generic. Some thought the new pill was a different medicine. Others worried the generic was weaker. Pharmacists spend hours each week explaining that the active ingredient is identical - just made by a different company, with different fillers or color.

How Hospital Pharmacies Handle Substitution

In a hospital, substitution doesn’t happen at the window. It happens in a conference room. Every hospital with more than 50 beds has a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee - a group of doctors, pharmacists, nurses, and administrators who decide which drugs belong on the hospital’s formulary. This isn’t about cost alone. It’s about safety, effectiveness, and clinical pathways.

For example, a P&T committee might decide to switch from vancomycin to linezolid for treating MRSA infections. Why? Because linezolid has fewer kidney side effects, is easier to dose, and reduces the risk of antibiotic resistance. But this change isn’t made by one pharmacist. It’s approved by the committee, documented in policy, and rolled out with training for every unit. When a doctor writes an order for vancomycin, the EHR system might pop up: "Alternative available: linezolid. Approved by P&T on 1/15/2026. Requires physician acknowledgment."

Unlike retail substitution, hospital substitution isn’t automatic. It’s clinical. And it’s not limited to pills. Hospitals substitute IV antibiotics, biologics, and even compounded IV bags. In fact, 68.4% of hospital therapeutic interchanges involve injectable or complex formulations - something retail pharmacies rarely touch.

When a substitution happens in the hospital, the system tracks it. The change goes into the electronic health record. Nurses see it. Doctors get alerts. Pharmacists review it daily. If a patient is transferred from the ICU to a regular floor, the new team knows exactly why their medication changed. There’s no guessing.

Why the Rules Are So Different

The split between retail and hospital substitution goes back to the 1965 Hospital Pharmacy Services Act. That law created two separate worlds: one for community pharmacies serving individuals, and one for institutional settings serving patients within a coordinated care system.

Retail pharmacies answer to state boards of pharmacy and private insurers. Their goal is to fill prescriptions quickly and cheaply. Hospital pharmacies answer to the Joint Commission, CMS, and their own clinical teams. Their goal is to improve outcomes, reduce errors, and manage drug use across a whole system.

This means the legal authority is different. A retail pharmacist can substitute without asking anyone. A hospital pharmacist can’t - not even if they think it’s a better choice. They need committee approval. Even then, the doctor must be notified within 24 hours. That’s a Joint Commission requirement. In retail? No such rule.

The technology is different too. Retail pharmacies use basic dispensing software. Hospital pharmacies use EHRs with clinical decision support. These systems can flag drug interactions, check renal function, suggest alternatives based on lab results, and even auto-replace a drug if a patient’s creatinine level rises. That kind of intelligence doesn’t exist in a retail pharmacy’s system - and it’s not designed to.

What’s at Stake: Safety, Cost, and Confusion

The stakes in each setting are different. In retail, the biggest risk is patient misunderstanding. A 72-year-old woman switches from brand-name Plavix to generic clopidogrel. She reads the new label. The pill looks different. She stops taking it, thinking it’s not the same. She has a stroke. That’s not a hypothetical. It’s happened.

In hospitals, the risk is fragmentation. A patient is discharged after being treated with a hospital-formulary antibiotic. The discharge script says "amoxicillin-clavulanate." But the retail pharmacy doesn’t carry that exact brand. The pharmacist substitutes a different generic. The patient’s doctor didn’t know about the hospital’s substitution. The new pharmacist didn’t know the patient’s history. The result? A medication error during transition. According to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, 23.8% of medication errors during hospital-to-home transitions involve substitution mismatches.

Cost savings are huge - but uneven. Retail substitution saves $317 billion a year. That’s mostly from generics replacing brand-name drugs. Hospital substitution saves 18.7% on medication costs per patient - not because of generics, but because of therapeutic interchange. Swapping a $2,000 IV drug for a $600 alternative that works just as well saves money without compromising care.

Who’s Doing It Right?

Some hospitals are building bridges. Forty-eight percent now have formal medication reconciliation programs that include substitution history from the hospital stay. That means when a patient goes home, the discharge summary says: "Vancomycin was switched to linezolid on 1/10/2026 per P&T protocol. Recommend continuing linezolid."

Some retail chains are catching up. Thirty-seven percent now offer discharge follow-up calls to patients who were hospitalized. They ask: "Did your doctor change your meds while you were in?" They check the prescription against the hospital’s records. If there’s a mismatch, they call the prescriber.

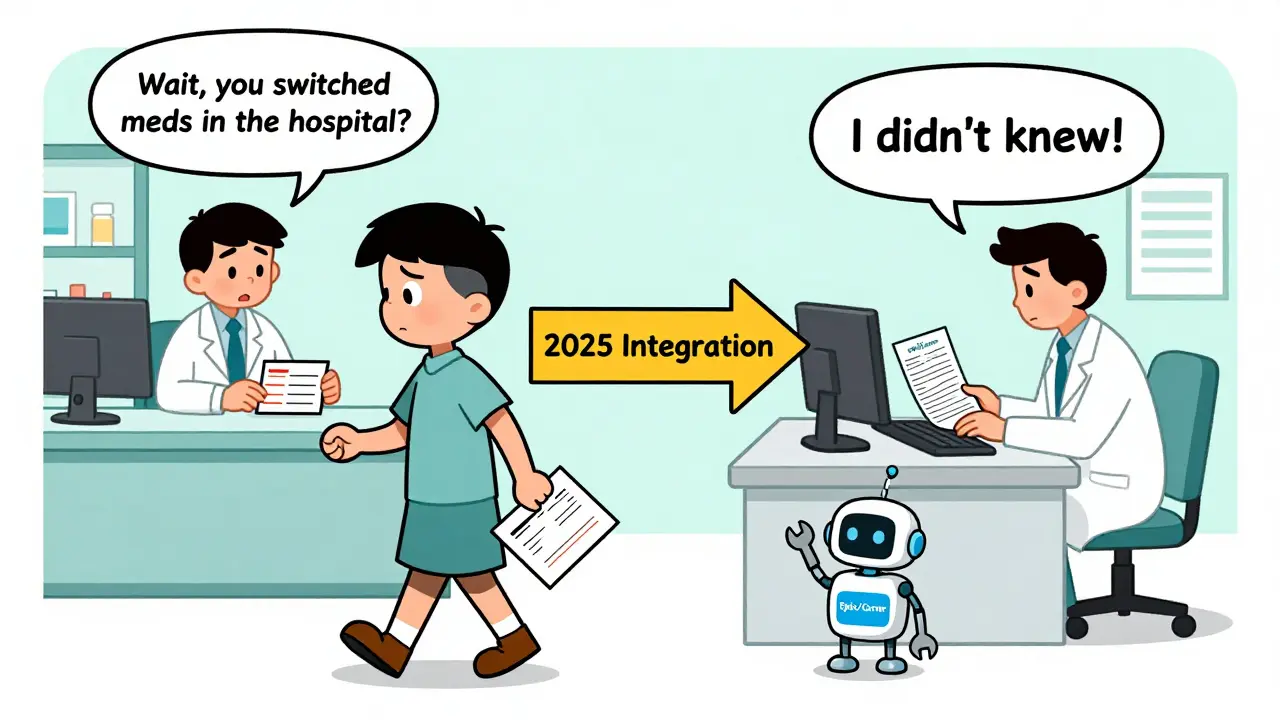

By 2025, Epic and Cerner - the two biggest hospital EHR systems - will start sharing substitution history between hospital and retail pharmacies. That’s a big deal. It means a pharmacist at CVS might see: "Patient switched from amoxicillin to cephalexin in hospital on 1/12/2026. Continue cephalexin."

This isn’t just convenience. It’s safety. When substitution practices are aligned, errors drop. Readmissions drop. Costs drop.

What Pharmacists Need to Know

If you’re a retail pharmacist, your job is to know your state’s laws, your insurance partners’ rules, and how to talk to patients. You need to explain why a generic is safe. You need to handle refusals. You need to manage prior auth delays. It’s not glamorous, but it’s vital.

If you’re a hospital pharmacist, your job is to know the formulary, the P&T process, and how to convince doctors to change. You need to understand clinical data. You need to train teams. You need to make sure the EHR works right. It’s complex. It’s slow. But it’s where the most impactful substitution happens.

The truth is, both roles are essential. Retail substitution keeps drugs affordable. Hospital substitution keeps care safe. The gap between them is shrinking - but it hasn’t disappeared. Until it does, pharmacists on both sides must stay sharp, stay informed, and stay connected.

Can a retail pharmacist substitute any generic drug?

No. Retail pharmacists can only substitute drugs that are deemed therapeutically equivalent by the FDA and allowed under state law. Some drugs, like warfarin or levothyroxine, have narrow therapeutic windows, and many states restrict substitution for these. Also, if the prescriber writes "Do Not Substitute" or the patient refuses, substitution is not allowed.

Why do hospitals use therapeutic interchange instead of simple generic substitution?

Hospitals use therapeutic interchange because they’re focused on clinical outcomes, not just cost. A hospital might substitute one brand-name drug for another brand-name drug - or a brand for a generic - if the alternative has better safety, fewer side effects, or fits better into a treatment protocol. This requires clinical review, not just a price check.

Are biosimilars substituted differently in hospitals versus retail?

Yes. In retail, 23 states have laws allowing pharmacists to substitute biosimilars for biologics - similar to generic substitution. But in hospitals, biosimilar substitution is handled through P&T committees, often requiring physician approval and documentation in the EHR. Hospitals are more cautious because biologics are used for serious conditions like cancer or autoimmune diseases.

Do hospital pharmacists have the authority to substitute without approval?

No. Hospital pharmacists cannot make substitution decisions on their own. All therapeutic interchange must be approved by the Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee. Even then, substitutions are often implemented as protocols - meaning the EHR suggests the alternative, but the prescriber must acknowledge and accept it.

What happens if a patient is discharged from the hospital with a substituted medication?

The discharge summary should clearly state the substitution and the reason. If the retail pharmacy doesn’t carry the same brand or generic, the pharmacist may need to contact the prescriber to confirm the change. Without clear communication, patients risk being switched again - often to a less appropriate drug - leading to errors or adverse effects.

Comments (9)

Joy Johnston

5 Feb, 2026Just wanted to say this post nails it. The retail vs hospital divide isn't just about cost-it's about context. In retail, you're a cog in a machine that moves pills fast. In hospital, you're part of a team that saves lives, one dosing decision at a time. I've seen both sides, and the clinical rigor in hospitals? It's humbling. Pharmacists there don't just fill scripts-they prevent disasters.

The P&T committee model? Brilliant. It's not bureaucracy-it's layered safety. When a drug gets swapped, it's because a dozen experts reviewed the data, not because a computer flagged a cheaper option. That's why hospital errors are lower, even with more complex meds.

And don't get me started on discharge transitions. So many patients get handed a script that doesn't match what they were on inpatient. No one talks about how often that leads to readmissions. We need standardized substitution logs in EHRs, period.

Amit Jain

6 Feb, 2026Simple truth: retail = fast and cheap. Hospital = slow and safe. Both matter. In India, we don’t have generics everywhere, so when we do, we check twice. In hospitals here, we use only what the committee says. No guesswork. No shortcuts. Patient lives are not a cost-saving experiment.

Katherine Urbahn

7 Feb, 2026It is, without question, a moral failing that retail pharmacists are permitted to substitute medications without patient consent in 12 states. The FDA’s therapeutic equivalence designation is not a license for negligence. When a 72-year-old woman stops taking her 'different-looking' pill because she was never informed, and subsequently suffers a stroke-this is not an accident. It is a systemic failure of professional ethics. The law must change. Immediately.

Furthermore, the notion that 'cost savings' justify this practice is ethically bankrupt. If a drug is labeled 'therapeutically equivalent,' then why does the patient need to be informed? Because equivalence is not identity. Fillers matter. Manufacturing processes matter. And the patient’s autonomy must be prioritized over corporate profit margins. Always.

I am appalled that 37% of retail chains now offer follow-up calls. That’s not progress-that’s damage control. We should never have allowed this system to exist in the first place. The burden of education should not fall on the pharmacist. It should be mandated by federal regulation. Period. End of discussion.

Keith Harris

9 Feb, 2026Oh please. You're all acting like hospital pharmacists are saints and retail ones are criminals. Newsflash: the hospital 'P&T committee' is just a bunch of MDs and pharmD PhDs who think they're smarter than everyone else. They sit around for 6 months debating whether to swap one $1,200 drug for another $1,150 drug. Meanwhile, the guy at CVS is getting yelled at by a grandma because her 'Lipitor' looks like a blue marble now.

And let’s not pretend hospitals are this flawless utopia. I worked in one. Half the time, the EHR auto-substitutes because someone forgot to disable the default setting. Nurses don't even read the alerts anymore. They just click 'acknowledge' and move on. So much for 'clinical rigor.' It's all theater.

The real problem? Insurance companies. They're the ones forcing substitutions everywhere. Retail? Insurance. Hospital? Insurance. The only difference is that hospitals hide it behind committees and jargon. Wake up. It's all the same game. You're just changing the color of the cage.

Mandy Vodak-Marotta

10 Feb, 2026Okay so I’ve been a pharmacy tech for 12 years and I’ve seen EVERYTHING. Retail is chaos, but it’s chaotic in a way that keeps millions of people alive every day. I’ve had people cry because they couldn’t afford their brand, and then light up when we switched them to generic and they saved $400. That’s real. Real human impact.

But then I worked a 3-month rotation in a trauma hospital and holy heck-there’s a whole other universe. One time, a patient on vancomycin had a creatinine of 4.8. The pharmacist didn’t just swap it-she pulled up the renal dosing calculator, ran the numbers, checked the patient’s history, called the ID team, and proposed linezolid with full documentation. I’ve never seen anything so deliberate. It felt like watching surgery.

And yeah, discharge transitions are a nightmare. I had a guy come in last month with a script for amoxicillin, but his hospital record said he was on cephalexin. The retail pharmacist had no idea. He was allergic to penicillin. The hospital had switched him because of that. But no one told the outpatient pharmacy. He almost got hospitalized again. That’s not a glitch. That’s a system failure.

What’s gonna fix it? Tech. Epic and Cerner finally talking to each other? YES. We need a universal substitution log. Like a blockchain for meds. Every change, every reason, every doc’s note-visible to every pharmacy, every EHR, every patient portal. Imagine that. No more guessing. No more strokes. Just clarity. I’d pay for that app.

Alec Stewart Stewart

10 Feb, 2026Hey everyone, just wanted to say thanks for this thread. I’m a new grad pharmacist and this helped me see the big picture. I thought retail was just 'fill and go'-but now I get how much patient education matters. One lady asked me why her pill was yellow instead of blue. I spent 10 minutes explaining generics. She hugged me. That’s why I do this.

And hospitals? Man, I shadowed one last month. The P&T committee meeting was like a science symposium. They had graphs, case studies, even patient outcome data. I didn’t realize how much thought went into every swap. It’s not about money. It’s about safety. And yeah, the discharge handoff is broken-but I’m working on a project to fix it at my school. Small steps.

To the guy who said 'it's all theater'-I get it. But I’ve seen both. And I can tell you: the hospital team? They’re not faking it. They’re just tired. And they need our support. Not cynicism.

Let’s keep talking. We’re all on the same team. 🙏

Geri Rogers

11 Feb, 2026YESSSSS!!! 🙌 This is the most important thing I’ve read all year!! You’re so right about the P&T committees-they’re the unsung heroes of healthcare!! 🏥✨

I’ve been a hospital pharmacist for 15 years and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve argued with a doctor who wanted to keep a $3,000 drug because 'it’s what the patient was on.' I said: 'Sir, this patient has stage 3 kidney disease. We switched to the biosimilar because it’s 70% cheaper AND has fewer nephrotoxic effects. You’re not saving them-you’re risking them.' He finally agreed. We saved $18,000 that month. And the patient? They’re doing great.

And retail? UGH. I had a patient yesterday come in asking why her 'new' blood pressure med was 'not working.' Turns out, her hospital switched her from a brand to a generic. But the retail pharmacist didn’t call the doctor. She just handed it over. She’s now in the ER with dizziness. I’m so mad.

WE NEED A NATIONAL STANDARD. NOW. 🗣️💊 #PharmacistsUnite #StopTheSubstitutionGap

Samuel Bradway

13 Feb, 2026Just wanted to say I appreciate this. I’m a nurse, and I see the fallout from this stuff every day. Patients come back confused, scared, sometimes sicker. I’ve had to explain to families why their mom’s meds changed twice in two weeks. It’s exhausting.

But honestly? Most of us just want to do right by our patients. The system’s broken, not the people. The pharmacist at CVS? Probably just trying to get through her shift. The hospital team? Probably working 12-hour days with no coffee.

Let’s fix the system. Not blame the workers.

Amit Jain

15 Feb, 2026Good point. But in many countries, even this system doesn't exist. We need global standards too.