For decades, pharmacists were seen as the people who handed out pills from behind the counter. But today, in many parts of the U.S., they’re doing far more-adjusting prescriptions, switching medications, even prescribing birth control or naloxone without a doctor’s direct order. This shift isn’t just a trend; it’s a legal and clinical evolution happening state by state. Understanding what pharmacists can and cannot do under pharmacist substitution authority matters because it affects how quickly you get care, how much you pay, and who’s responsible when things go wrong.

What Exactly Is Pharmacist Substitution Authority?

Pharmacist substitution authority means the legal right to change a prescribed medication under specific conditions. It’s not about guessing or improvising. It’s a structured, regulated power granted by state law. The most basic form is generic substitution: if your doctor prescribes Lipitor, and there’s a generic version of atorvastatin available, the pharmacist can give you that instead-unless the doctor specifically wrote “dispense as written.” This is allowed in every state. But it goes further. In some states, pharmacists can swap a drug for another in the same therapeutic class-like switching from one statin to another-even if they’re not chemically identical. That’s called therapeutic interchange. It’s not automatic. The prescriber must explicitly allow it on the prescription. In Kentucky, they must write “formulary compliance approval.” In Arkansas and Idaho, they must say “therapeutic substitution allowed.” And in Idaho, the pharmacist has to explain the change to you, in plain language, and make sure you’re okay with it.How States Differ: A Patchwork of Rules

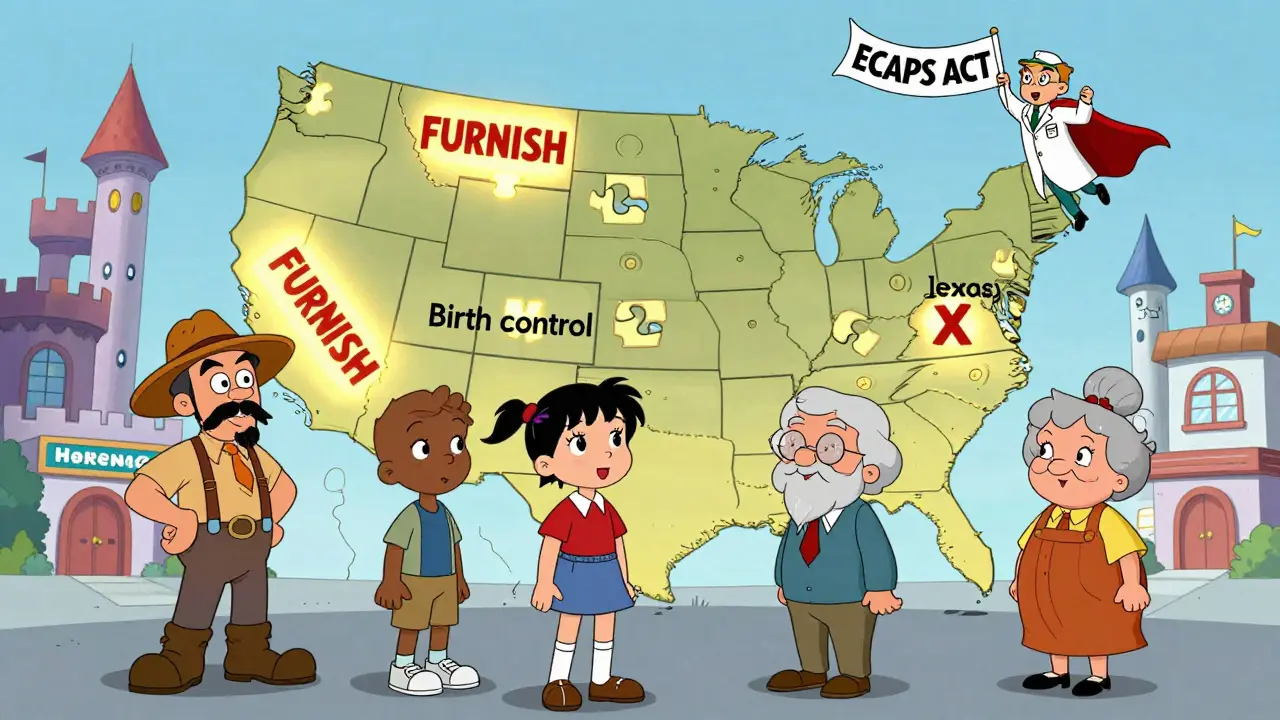

There’s no national standard. What’s legal in California isn’t allowed in Texas. That makes it confusing for patients and pharmacists alike. Some states have gone further. Maryland lets pharmacists prescribe birth control to anyone over 18. Maine allows them to hand out nicotine patches without a prescription. California doesn’t use the word “prescribe”-they say “furnish.” That’s a legal workaround to avoid clashing with medical licensing laws. New Mexico and Colorado let their Board of Pharmacy set statewide protocols. That means pharmacists can offer certain services-like flu shots or diabetes testing-without needing a new law passed every time a new drug is added. The most advanced model is independent prescribing under protocol. All 50 states and D.C. now let pharmacists prescribe or dispense medications under a standing order or protocol for at least one condition. That could be emergency contraception, travel vaccines, or opioid overdose reversal. In these cases, the pharmacist doesn’t need to call a doctor. They follow a pre-approved checklist: patient age, symptoms, vital signs, drug interactions. If it fits, they act. If not, they refer.Collaborative Practice Agreements: The Middle Ground

Many states use Collaborative Practice Agreements (CPAs) to expand pharmacist roles. These are formal, written agreements between a pharmacist and one or more physicians. They outline exactly what the pharmacist can do: adjust blood pressure meds, start anticoagulants, manage diabetes, order lab tests. The agreement includes when to refer back to the doctor, what records to keep, and how to communicate changes. CPAs are growing. More states are letting pharmacists drive the protocol instead of waiting for the doctor to initiate. That’s a big shift. It means pharmacists are no longer just executors of orders-they’re active participants in care teams. But implementation varies wildly. In some clinics, CPAs are routine. In others, they’re rare because doctors don’t have time to sign them, or insurance won’t pay for the service.

Why This Matters: Access, Equity, and Shortages

The push for expanded authority isn’t about pharmacists wanting more power. It’s about people who can’t get care. Sixty million Americans live in areas with too few doctors-rural towns, inner cities, places where the nearest clinic is an hour away. For someone with high blood pressure, a trip to the doctor every month isn’t practical. But a pharmacy down the street? That’s doable. Pharmacists can monitor blood pressure, adjust meds under a CPA, and call the doctor only if something’s wrong. That keeps people on treatment. It prevents hospital visits. The same goes for birth control. In states where pharmacists can prescribe it, young women get pills faster. No waiting for an appointment. No missed doses. No unintended pregnancies. Studies show these programs work. They’re safe. And they save money. The American College of Clinical Pharmacy says pharmacists are uniquely trained to manage medications. We know how drugs interact. We spot side effects. We catch errors. When you add clinical judgment to dispensing, outcomes improve.The Pushback: Who’s Against It?

Not everyone supports this change. The American Medical Association still has a policy to study pharmacists refusing to fill prescriptions-hinting at lingering tension over professional boundaries. Some doctors worry pharmacists aren’t trained enough to make clinical decisions. They point out that medical school is four years, plus residency. Pharmacy school is four years, plus optional residencies. The training is different, not necessarily lesser. Another concern is corporate influence. Big pharmacy chains like CVS and Walgreens have lobbied hard for expanded authority. Critics say they’re pushing it to boost profits-turning pharmacies into mini-clinics to drive foot traffic. There’s truth to that. But the solution isn’t to stop progress. It’s to make sure regulations are strong, transparent, and patient-centered.

Comments (11)

Sarah McQuillan

18 Dec, 2025Look, I get that pharmacists are smart, but let’s not pretend they’re doctors in scrubs. I’ve seen too many people get mixed up on meds because some guy behind the counter thought ‘statins are statins.’ This isn’t progress-it’s a liability waiting to happen. And don’t even get me started on the corporate agenda behind all this. CVS wants you to buy protein shakes while you wait for your blood pressure script. That’s not healthcare. That’s retail.

Kitt Eliz

18 Dec, 2025OMG YES 🙌 This is the future of primary care!! Pharmacists are underutilized clinical powerhouses!! 🚀 With their pharmacokinetic expertise + patient counseling skills + accessibility? They’re literally the missing link in our broken system. States like CA and NM are leading the charge with protocol-driven prescribing-no more waiting 3 weeks for a doc appointment just to refill your metformin!! Let’s fund this, scale this, and stop letting siloed MDs gatekeep care!! 💊📈 #PharmacistPower #InterprofessionalCare

Aboobakar Muhammedali

19 Dec, 2025i read this and i just feel so happy for people who live in places where this is possible. in my country we still need a doctor to write every little thing even for a cold. i remember my cousin had to wait two weeks just to get antibiotics because the clinic was full. i wish more places could see how simple and safe this is. pharmacists know their drugs better than anyone. they dont need to be doctors to help people

Laura Hamill

20 Dec, 2025So let me get this straight… Big Pharma and CVS are pushing this so they can make more money? And now pharmacists are basically doctors but without the 8 years of training and the liability? Sounds like a scam to me. Next they’ll be doing MRIs and writing death certificates. Wake up people-this is how they privatize healthcare. You think they care about your blood pressure? They care about your insurance card. They’re turning pharmacies into clinics so they can bill Medicare for stuff they shouldn’t even be doing. This isn’t progress. It’s corporate takeover.

Alisa Silvia Bila

21 Dec, 2025I’ve had my blood pressure adjusted by my pharmacist twice now. No drama. No waiting. Just a quick chat, a quick check, and a new script. It works. Why are we fighting this?

Marsha Jentzsch

22 Dec, 2025Wait-so now pharmacists are prescribing birth control?? Without a doctor?? And you’re just okay with this?? What if they make a mistake?? What if they don’t know your history?? What if they’re just tired and rush through it?? I mean-this is MY BODY we’re talking about!! And now some guy in a white coat is deciding what hormones I get?? This is insane!! Who’s responsible if something goes wrong?? I’m not some lab rat for this experiment!!

Danielle Stewart

23 Dec, 2025As someone who’s been managing diabetes for 12 years, I can’t tell you how much easier it is to swing by the pharmacy and get my metformin adjusted after my A1C comes back high. No appointment. No copay. Just a pharmacist who knows my meds better than my doctor does sometimes. This isn’t about replacing doctors-it’s about giving patients more access, more consistency, and more dignity. Thank you to every pharmacist who’s stepping up.

Glen Arreglo

25 Dec, 2025I’ve worked with pharmacists in three states now. The ones who do therapeutic substitution? They’re meticulous. They check interactions, document everything, and explain changes in plain language. They’re not trying to be doctors-they’re trying to help people who can’t get care. This isn’t a threat. It’s a solution. Let’s stop the fear and start the collaboration.

shivam seo

27 Dec, 2025Let’s be real-this whole thing is just a way for pharmacy chains to make more money. You think they care about your hypertension? They care about your loyalty card. They want you to buy snacks while you wait for your statin. And don’t even get me started on the liability. Who’s paying when someone has a stroke because a pharmacist swapped a med without checking their kidney function? Nobody. That’s who. This is lazy healthcare dressed up as innovation.

benchidelle rivera

28 Dec, 2025As a clinical pharmacist with 18 years of experience, I can confirm: the protocols in place are rigorous, evidence-based, and patient-centered. The ECAPS Act is not just important-it’s essential. Reimbursement is the barrier, not competence. We are trained to manage chronic disease, prevent adverse events, and optimize outcomes. The data supports this. The patients support this. It’s time for policy to catch up.

Matt Davies

30 Dec, 2025Pharmacists are the unsung heroes of the healthcare system. They’re the ones who catch the 17 drug interactions your doc missed, who remind you to take your pills, who know your kid’s asthma inhaler better than you do. This isn’t some corporate plot-it’s common sense. If you’ve got a pharmacy on every corner and a doctor shortage in every county, why aren’t we using the smartest people in the building? Let’s stop treating them like glorified cashiers and start treating them like the clinicians they are.